From 3.5 Acres to a Legacy: The Remarkable Story of Madison's Park System

- Jessica Benitez

- Nov 14, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2025

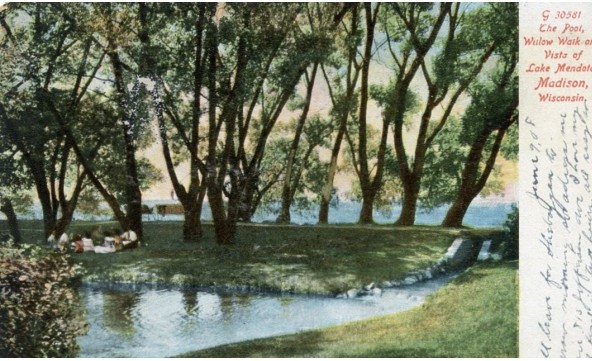

When you stroll through Tenney Park on a summer afternoon, kayak past Vilas Beach, or bike along Lake Mendota Drive, you're experiencing more than just beautiful green spaces. You're walking in the footsteps of visionaries who, over a century ago, transformed Madison from a city with barely any parkland into one of America's most park-rich communities. This is the story of how a small group of determined citizens created a legacy that continues to shape our city today.

A City With Almost Nothing

It's hard to imagine now, but in 1892, Madison had just 3½ acres of park land. That's it. The only park was Orton Park, named after former mayor and Supreme Court Justice Harlow S. Orton, which had originally served as a burial ground before the plots were moved to Forest Hill Cemetery in 1856. For a city blessed with extraordinary natural beauty—situated on an isthmus between two lakes—this was nothing short of tragic.

The Birth of a Movement

On April 27, 1892, University of Wisconsin Professor Edward T. Owen sparked a conversation that would change Madison forever. He proposed creating an organization to develop "rustic roadways through picturesque scenery in and about Madison" and to acquire parks beyond the city limits. Two years later, on July 10, 1894, the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA) was formally organized with just 26 members and $655 in initial subscriptions. There was no precedent for such an organization—they were inventing something entirely new. Professor Owen put his money where his vision was, personally purchasing 14 acres extending from the Catholic cemetery through the William Larkin Farm around Sunset Point for $3,000. He paid for both the land and the improvements himself. Today, we know this area as Hoyt Overlook.

The Man Who Made It Happen

While several people were instrumental in Madison's park movement, one name stands above the rest: John M. Olin. When Olin began his work in 1894, Madison had those 3½ acres and no Park Commission. By the time he stepped back in 1909, the city boasted 269 acres of parkland, three pleasure drives, a Park Commission, and a nationally recognized parks organization. In those 15 years, Olin persuaded Madisonians to voluntarily contribute nearly a quarter of a million dollars—an astronomical sum in early 1900s money.

In his own words, captured in his diary, Olin wrote: "We have a natural advantages unsurpassed by any other city in the State, and we have felt for some time that if we keep up with the procession we must adorn what nature has done for us in making our city more beautiful by art and for the pleasure of the many instead of lesser pleasure for the few."

His philosophy was simple but profound: beautiful public spaces shouldn't be just for the wealthy. Everyone deserved access to nature and recreation.

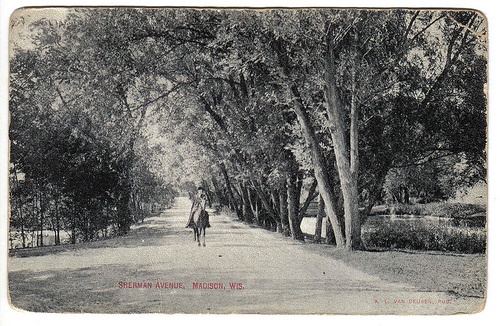

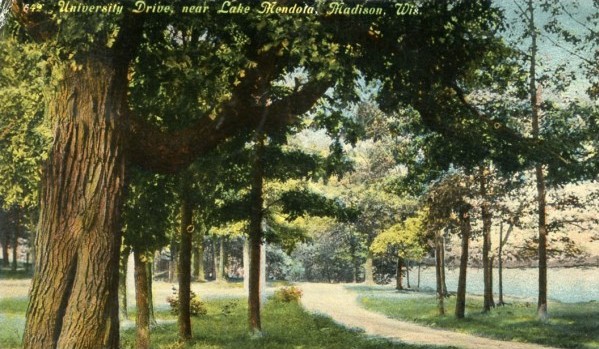

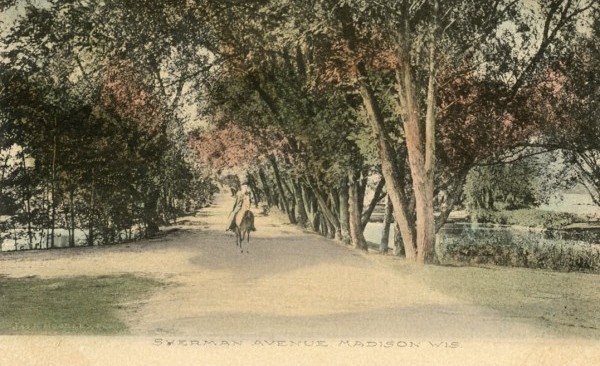

The Pleasure Drives: Roads Designed for Joy

One of the most fascinating aspects of the MPPDA's work was the creation of "pleasure drives"—scenic roadways designed for leisurely travel through beautiful landscapes. The Association proposed four drives: from the University to Picnic Point, around Lake Mendota, from Sherman Avenue to the hospital, and around Lake Monona. George Raymer, founder of University Press, was an early ally, opening his land to the public in 1881 as Raymer Road along Lake Mendota's shore—now Lake Mendota Drive.

Here's a quirky historical detail: motor vehicles were initially banned from the parkways. When automobiles were finally permitted in 1903, it was only on specific days and times. You could drive on the west and south drives on Tuesdays after noon and Thursdays before noon, and on the north and east drives on Wednesdays before noon and Fridays after noon. Imagine trying to plan your Sunday drive around that schedule!

Tenney Park: Madison's First Major Park

The story of Tenney Park beautifully illustrates the collaborative spirit behind Madison's park system.

In 1899, businessman Daniel Kent Tenney made an extraordinary offer: he would purchase land and contribute $2,500 for park development if the Association would hold it in trust for the city, develop it for public use, and raise another $2,500 from other sources. Olin rallied support, the Association raised $1,000, and the City Council contributed $1,500. The deal was done. What started as 14 acres grew to 44.2 acres by 1910, with land and money gifts from Tenney, Joseph Hausmann, and the Willow Park Association. The park's lagoons—now iconic features—were all artificial, dug by horse power. In 1901 alone, 6,850 trees and shrubs were planted.

The park evolved with the times:

1903: Footpaths and bridges over the lagoons

1907: Locks allowing boats to travel between the lake and Yahara River

1910: Sunday afternoon band concerts (alternating with Vilas Park)

1913: Rebuilt bathhouse serving 300 people daily

1915: Six tennis courts

1918: Skating rinks

1921: Playground supervisors

1923: Lifeguards and swimming instructors

Daniel Kent Tenney's generosity didn't end with his lifetime—his will included provisions for $500 to be donated annually to the park's development.

Vilas Park: A Father's Memorial

In 1904, Senator William Freeman Vilas—who had served as Postmaster General, Secretary of the Interior, and U.S. Senator—contributed $18,000 to purchase 25 acres between Randall Avenue and Edgewood Avenue. The park was named not after the senator himself, but after his son Henry, who had died of diabetes as a young man. It was both a public gift and a private memorial.

Senator Vilas continued his support, donating two stone and concrete bridges over the lagoon in 1906 for $5,000. After his death in 1908, his widow Anna M. Vilas donated $25,000 in 1910 for additional land to expand the park. In 1911, Thomas C. Richmond donated a herd of five Wisconsin white-tail deer from his south Madison home, creating an enclosure in the park. Madison's zoo was born.

The park required massive planting efforts: in 1908 alone, over 300 trees and shrubs from Association nurseries were planted, along with 765 purchased shrubs and over 15,000 gathered from the wild.

Brittingham Park: Transforming an Eyesore

Not every park started with pristine land. The area known as "the triangle" had become home to a row of ugly, shanty-like boathouses when Thomas Evans Brittingham stepped in.

In 1905, Brittingham offered the Association $8,000 for improvements if they could raise an additional $10,000 through public subscription. The community came through, and the transformation began.

Brittingham's generosity continued:

1908: $7,500 for a boathouse designed by John Nolen

By 1911: Total contributions of $24,500

The park required planting 17,000 trees. By 1915, it featured six tennis courts and a baseball field. By 1923, the city was providing swimming instructors and lifeguards at the beach.

The Green Network Grows

The MPPDA's acquisitions throughout the early 1900s were relentless:

1900: 10 acres for what became Wingra Park (first called Conklin Park, then Washington Park)

1902: Proposal to acquire the entire Yahara shore for a parkway, aided by a donation of 1,650 feet of shore from the Hausmann Brewing Company

1903: Shoreline donation from Mrs. Elisha Burdick

1904: Halle Steensland contributed $8,000 for the stone and concrete Steensland Bridge over the Yahara River

1905: Acquisition of what's now B.B. Clarke Park (Monona Park) for $5,300

By 1908, the Association had planted more than 140,000 trees, shrubs, and vines throughout the parks and along the pleasure drives. These came from purchases, donations, wild gathering, or the Association's own nursery operated on what is now Burrows Park.

A Legacy That Lives On

When John Olin died in 1924 at age 73, fellow Association member Michael Olbrich called him "the father of Madison's Park System." It was a well-deserved title. But Olin's vision extended beyond his own lifetime. Before his death, he established the John Olin Trust, which still administers and supports Madison's parks today—a century later. It was his final gift to ensure that future generations would continue to benefit from the green spaces he worked so hard to create.

In just 30 years, a small group of citizens with vision and determination had transformed their city. They understood that parks weren't luxuries—they were necessities for public health, community building, and quality of life. They believed that everyone, regardless of wealth, deserved access to beauty and nature.

Carrying the Torch Forward

Today, as Madison continues to grow and develop, we're still benefiting from the foresight of Olin, Owen, Tenney, Vilas, Brittingham, and countless other donors and volunteers who believed in the power of public green spaces.

Inspired by John Olin's commitment to sustaining parks for future generations, the Madison Parks Foundation has created the Parks For All Trust—a modern echo of Olin's original vision. The goal is ambitious: raise $10 million for a trust that could provide up to $500,000 in support each year to our parks, in perpetuity. Just as Olin and his contemporaries looked ahead to our generation, this new trust looks forward to the Madisonians of 2125 and beyond. It's proof that the spirit of civic generosity that built our park system in the early 1900s is alive and well today.

The challenge facing us is similar to the one Olin faced: will we be good ancestors? Will we ensure that future generations inherit parks that are as beautiful, accessible, and well-maintained as the ones we enjoy today?

Next time you enjoy one of Madison's beautiful parks, take a moment to remember: you're experiencing someone's gift to the future. You're living in the dream that John Olin and his colleagues made real. And you have the opportunity to pass that gift forward.

What's your favorite Madison park? Tell us on Facebook or Instagram! Learn more about supporting the Parks For All initiatives and becoming part of Madison's parks legacy.